Image + Word Interview 2: The Satanic Mechanic

Posted on March 25, 2020

For the second installment of Image + Word, PromptPress Intern Ethan Evans interviewed Iowa City-based cartoonist, printmaker, and artist-extraordinaire Violet Louisa Austerlitz.

Violet is a long-standing member of the Iowa City Press Co-Op, a community printmaking studio. She makes art about personal identity and the soil in which it grows, which then manifests itself as comics and other combinations of words and pictures. She frequently explores her own experience as a queer and trans person, both literally and through the medium of sentient dandelions. She is ambivalent about her formal education (BA Theatre, Printmaking Minor, Truman State University, 2011), but simply adores learning new things, and recently completed a workshop at the Center for Cartoon Studies in Vermont.

Ethan reached out to Violet to talk about her art practice at large and her comic, The Satanic Mechanic, which chronicles the lives of a demon blacksmith/auto mechanic, a dryad-drifter with dandelions growing out of their feet, and more.

After reading through The Satanic Mechanic, I was struck by the complexity of its characters, particularly Clover and Agnes. While a good deal of their personification comes from dialogue, parts are totally visual— I’m thinking here of the scenes where dandelions rise around Clover’s feet and out of their forehead. Do you think that this storytelling could be accomplished solely with word or with image?

Yes, probably, but at this point it would feel like something was missing. Up until a few years ago the bulk of my creative output was writing, and while I think I do okay with prose, working with comics has given me a more robust toolkit as a storyteller. I can really focus on the world the characters live in, and what they say to themselves and each other, and combine those things more gracefully and powerfully.

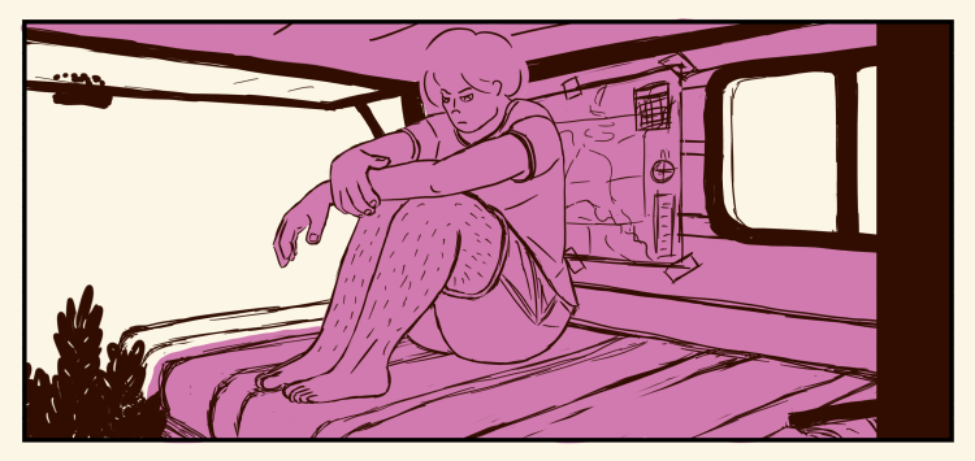

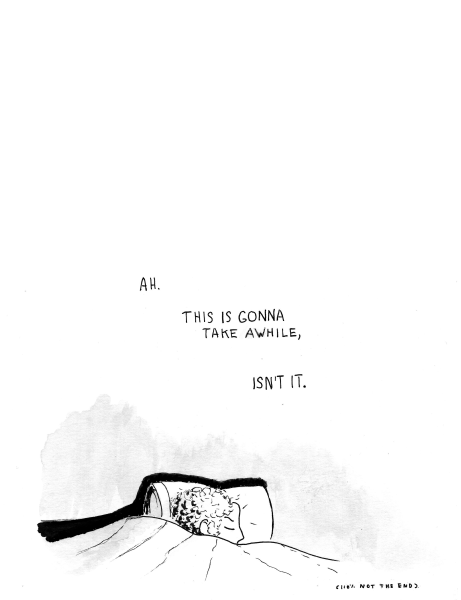

Seeing Clover sit hunched up in their truck while they wrestle with the possibility of allowing Agnes (or anybody, really) into their life carries more weight than trying to write out their whole thought process. You sit with them in that cramped camper shell and feel the time pass and watch them get sick enough of themselves that they finally accept help.

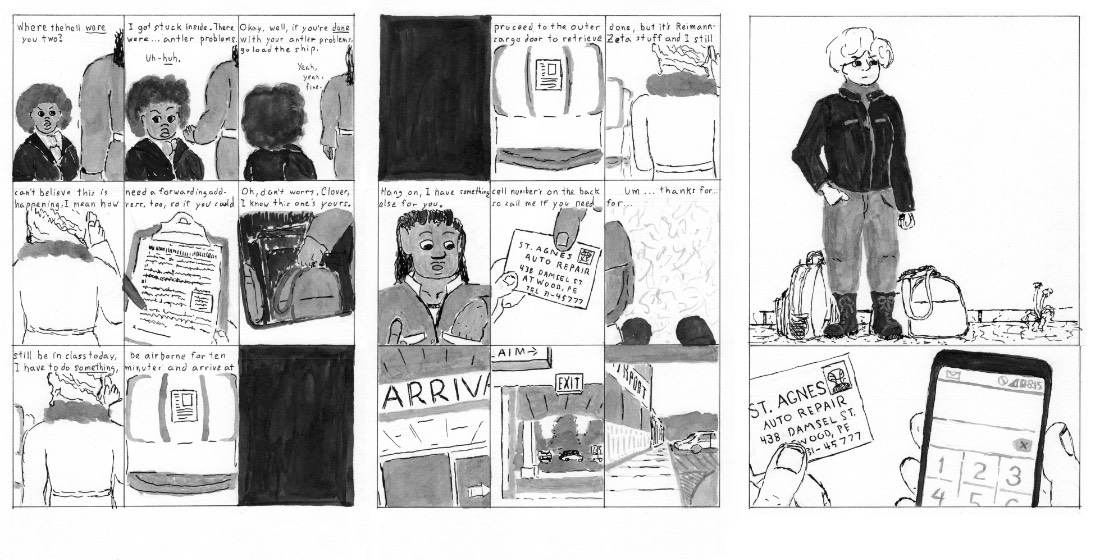

Leading in to that, we have Clover’s self-flagellating inner monologue and their reluctant first conversation with Agnes. That gives us a sense of the dynamic they share, as well as their differing attitudes and circumstances. It’s a chance to be specific and explicit with information, and see how characters really think. Only having one or the other of these elements would probably be fine, but I think word and image together fosters complexity and depth in a way that’s hard to match.

I’m interested in the relationship between the physical manifestations of The Satanic Mechanic and the digital ones. I know that the physical manifestation came first, and that it follows a different story arc. Do you see them as interrelated?

There’ve been a few different iterations of the characters and the story behind The Satanic Mechanic. The origin is far back in the mists of time, but the actual characters are from stuff that I wrote several years ago, and that was initially adapted as The Secret Desires of Elderly Buicks (which was my first actual finished comic book). Elderly Buicks was sort of a pilot episode; the next two books (Complete Failure and Ex-Succubus) explore the characters and the setting a little bit more. What is currently on the internet is the third iteration of that. That’s how I work; I tend to do a lot of writing this way, editing it and editing it and deciding to start completely over, so I can see what ideas actually carry through, and learn about my characters as I go. The version that’s running on the web now, which I’m going to try to make into a full length, completed story over however long that takes me, is something that I haven't really written ahead of time. It’s really more a process of exploring and figuring out the story as I go. The print versions were ways of figuring out the basics of how I make comics. I feel more confident in the technical parts of the online comic, so I can really focus on story and on developing the world around the characters.

Yes, especially during the first chapter, which I was working on last year. What I had originally written and thumbnailed was completely different from what ended up happening. There were a couple times when I realized it would be much simpler to do something else with the story, and that it would be just as effective. Which is really helpful with comics because comics take kind of a long time to make. It’s a very labor intensive process; wherever you can find simpler or more compact ways to tell the story it’s helpful to just do that and keep moving forward.

Are there any specific artists or works of art that inspired The Satanic Mechanic? Or your work at large?

There’s a lot. They’re all over the place. A big influence on me and on my work is Calvin and Hobbes, which was my favorite comic strip and favorite piece of media in general when I was a kid. I learned to read by reading Calvin and Hobbes. The comic strip was what made me want to create stuff. I think there’s a lot with the way Bill Waterson handled drawing, space in drawing, and story, because he was working within the very specific guidelines of a daily comic strip, that influenced me. Embracing limitations, in a way similar to Waterson, has been very important to my work.

Talking about my influences is somewhat tricky, because a lot of it is recognizable artists and writers, and a lot of it is just stuff I've seen on the internet. I’ve been hugely inspired by Steven Universe, and fanart and fanfiction related to it. It’s an extremely good show, and it’s what inspired me to start drawing again, which snowballed into me making my own comics. Steven Universe focuses on stories that are driven by character and emotion, and that are as much about relationships as they are about big plotlines. I think the show strikes a really interesting balance between those two things. The idea that you really can have both, and they really can reinforce each other isn’t something I’ve seen in a lot of other media, especially not cartoons.

There are also lots of other queer and trans people drawing comics online and elsewhere, which is really cool. It helps to make comics as a medium a really good space for talking about identity and expressing different experiences.

My practice as it currently exists started to take shape about three years ago when I decided to start making comics because I couldn’t decide whether to focus on writing or drawing. Once I began to discover the potential that comics have for exploring tricky emotional territory through visual metaphors (like exploring my fear of change with a dryad losing their job, or my fear of being known with lycanthropic car-eating behavior), it opened up the possibility of doing more personal, autobiographical work (like Femslash Chicken Awakenings) that similarly combined text and image to explore my place in the world and the way I was reimagining myself as a person.

It’s no coincidence that this period of time was also when I started to take hormones and go to therapy and do a great deal of personal work to change and grow as a person. The work functions as a visual diary of that time period and made a good space to play in while I grappled with who I was, who I am, and who I want to become.

Much of the first self-consciously queer literature I read was visual in nature— stuff like Alison Bechdel’s comics and the countless zines I picked up. Do you think queer folx are drawn specifically to these forms?

I don’t know if there’s a connection between specifically queer literature and visual forms, comics particularly, but I do wonder if the sort of underground cultural nature of queerness and the underground art forms of alt comix and zines attracted each other because they both were in an outsider position. And I also wonder if there’s an element of our feeling invisible, because we don’t see ourselves in most media, that pushes us to create that visibility, literally and figuratively. I would be fascinated to hear what other queer artists and writers think about this.

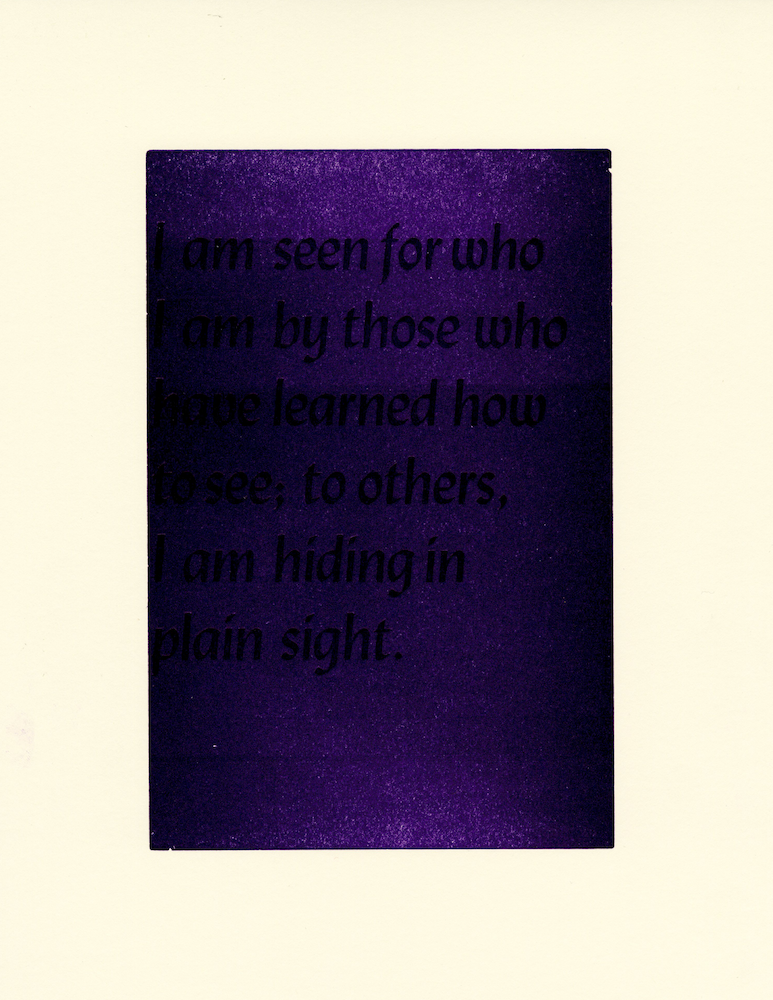

Personally, making self-consciously queer visual literature allows me to do something tricky - it allows me to precisely articulate certain ideas with text while conveying these really big hard-to-define feelings with images. I can talk very specifically about the things that came together to make me realize that I’m trans and at the same time viscerally illustrate some of the feelings involved in that moment. I can say something poetic about the experience of being misgendered all the damn time and make an image that the viewer can’t correctly read at first glance to counterpoint it.

I'm wondering if you could talk about the role of food and recipes in your work? I’m thinking both of Recipe for an Epiphany and Femslash Chicken Awakenings.

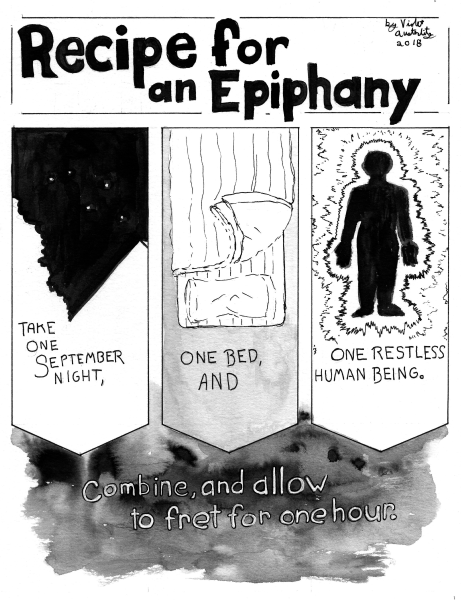

Femslash Chicken Awakenings is from a couple of years ago. I made it for the first Iowa City Press Co-Op print exchange, which had a cookbook theme. Originally I was playing off of the formats and conceits of recipe blogs, both in their visual layouts and propensity for massively oversharing about personal stuff. I was like, I can use this format to massively overshare about personal stuff, too! It also felt like a good format to work in at that time because I was still making sense of my identity. The format of a recipe, with ingredients coming together and changing into something new, was a really helpful framework. Recipe for an Epiphany was much less of a literal recipe, but still had that transformational moment. Recipes are all about process, which is how I think about things anyway. It’s been a really fun format to explore, though I think I’m done with it for now. My latest show seemed like a good stopping point for my current body of work, which included several explorations of identity like the recipe stuff. I may go back and experiment with it some more later, we’ll see.

So I was approached by a former college professor (Todd Coulter). He is currently in New York, having recently helped start an organization called NOGO Arts that works to promote LGBTQ+ artists and their work. He had read Recipe for an Epiphany in its comic form, and asked me if there was a way to adapt it into something that could be performed, since their inaugural show included several pieces with movement and spoken word. Since they didn’t have the budget for me to be in New York for a week (even though that would have been very cool), we decided to do it as a video piece.

Recipe for an Epiphany isn’t completely text driven; the images very much lead in the way that I composed it. It felt like a natural evolution to adapt it into something that was much more performance driven. I had a basic idea of making cutouts and collaging them together, animating the process of drawing the comic and switching the text for narration. Using the collage elements, and borrowing some format ideas from recipe videos, helped tell both the story in the comic, and the story of making it.

It was fun! I hadn’t done much video stuff since college, so I experimented a lot, and got to try some things I hadn’t for a long time. It didn’t change the piece in any big material way, but I did discover some new things about it. Certain phrases jumped out more when spoken than they did written, and it gave me the opportunity to work with color. It felt like a natural fit; I think the results conveyed the story well.

That makes me think about how there are performative elements in static works. There’s a section of blank space in Recipe for an Epiphany, for example, that forces the viewer to pause. It almost feels like stage directions. Do you think, as someone who was trained in theater, that’s there a direct transition from written theater to making comics or other graphic works?

Yes! My formal training in theater leaned more technical than performative, but through my major I dabbled in everything. We learned to use multiple disciplines and bring them all together to make a greater whole, which is what theater is. I think there’s a lot from theater that I’ve been able to translate into the way I make comics, especially in terms of thinking about the physicality and performance of different characters.

There are a couple of pages that I drew in The Satanic Mechanic and the Complete Failure that were nine panels on a page. The narrative was jumping from one location to another and the idea was to feel like a marathon-type experience, where you’re doing one thing after another and it’s very overwhelming. But in the page immediately after that you meet a single panel, and it’s like you’re rushing, all this stuff is happening, and you reach your destination and... now what? That’s a moment you have to sit in for a minute. Using visual space to give that sense of time and speed, and the emotion that comes with it, is a very cool tool that I’m still learning how to manipulate. I really really appreciate it when I see it done well, in comics and in theatre, and I think that the reading experiences that really stand out to me in comics are similar to the experiences that stand out to me in theatre.

Wow! I should make comics. I’ve thought about it before but if feels so... intimidating.

It’s less intimidating for me now because I’ve made a lot of comics and know that I can do it. Still, knowing that a 24 page comic might take, given other responsibilities in my life, 4 months to draw is daunting. Short stories can take a long time to make, and I think in the world of webcomics that I’m working in, that’s a common frustration for both readers and creators. Webcomics are a very inefficient way to tell a story; it can feel like it takes a very very long time to get somewhere, and there have been times when I have really felt frustrated by that as a creator.

In response to that, though, I’m learning how to find a balance point between the way I work and the way I present the finished comics. For the last year or so of doing The Satanic Mechanic, I tried to do consistent weekly updates, but because I was sort of writing it as I went, I didn’t always have pages done ahead of time, and there ended up being some pretty long gaps between updates. Right now I’m working on the next chapter, which I’m going to try to finish completely before I start posting new pages again. Everybody who makes a webcomic handles it a little differently, you just have to learn the best way to keep going.

Violet’s website can be reached here. You can find her on instagram at @violet_austerlitz