Jennifer MacBain-Stephens, "Farm to Table"

A response to James Gouldthorpe

The hog pen is a womb. Laden with sweet grass before the great emptying of 1944. Caress the runt like a yarn doll, remove feces, freshen vegetable feed, firm finger strokes and chat her up. The meat tastes poor inside stressed beasts. Homely names like Sally, Flo, and Hildy are cliché but comforting. Half-wits still bleed the same. Death comes to us all, but it is the lick of the salt, the Benjamins, the Johnson’s harvest festival, that we use to file sow under dispensable. Like dribbling juice boxes, the fluid never ends. Plump back fat, attractive side slabs, smoked, buttered, swallowed. Good morning out of one side of the mouth while grasping short legs. Goose bumped into eternal hot sauce, singes the stomach lining. Human meat is stringy. Tell that to a shark.

We all need lots of fathers part one

Borrowed bifocals earned him a gut wound sharpening knives on the strop. Get too close and whiff the whisky remains in black chin stubble. Wears the same hat every day of his life. Even at 2 am stumbling home from McHale’s he hatted his head and on the couch where he slept, there slept the hat. One second hand wool blazer. One mustard dolloped tie. Smokes he rolled himself spill out from forgotten pocket square real estate. Not one to shave to crave a close cheek. Always red bumps and then pain. The fathers all salesmen with heirloom time pieces. Clocks lost at the track. Back to selling the sharpest tools in the shed.

We all need lots of fathers part two

Door swings open at dusk every day or never and this (I am told) builds character in Arkansas. It’s lovely just to drink Earl Grey and breathe at the kitchen table let alone connect with yang energy. Speed bumps jolt the torso awake. The to-do list of briefcase, handshake, and bloodless kiss. Bodies are a business transaction, loan numbers paid in increments, monthly installments of feed and sliced flesh. Too many hands to handle. The hands fall short of touching. Wifely capabilities canned in jam jars hold tea cakes and sneers with a spoiled milk chaser. Seedless, rotten eggs turn in the fridge, grow legs, walk away, slam the porch door shut for all sepia toned generations to hear.

Process Notes

In looking at the picture of the sow for my poem "Farm to Table," (with the pig on the left and the meat on the right,) it seemed very much a "before and after" display to me. I thought of what went into caring for an animal and naming it and how it ends up -- on a plate, or a slab, or hung from a hook, not unlike how humans end up eventually, their bodies put through various poses. We are all broken down into parts.

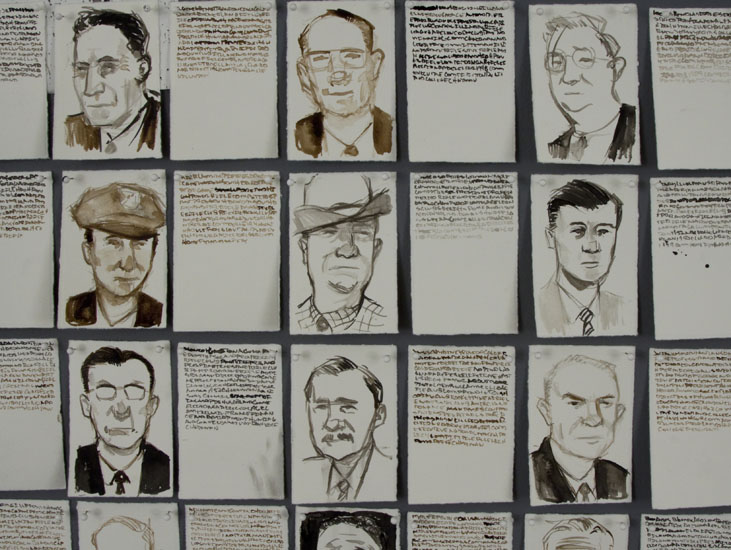

For "We all need lots of fathers, parts one and two," the construction of the male faces really struck me. Even with glasses, different hair cuts, beards, no beards, hats, ties, etc, they all held a similar expression in the eyes. This seemingly far away yet penetrating glance made me think about men/ fathers throughout time. The issues surrounding imperfections, the idea of "providing," possible inattention to women and children, infertility, these exist in such a linear fashion through time- despite clothing and accessory change-ups. When I look at the one image of the man with glasses, and I will never forget this face, I see one hundred men.

Responses to James Gouldthorpe's Work

Jennifer MacBain-Stephens

Jennifer MacBain-Stephens is the author of two chapbooks ("Every Her Dies," ELJ Publications, and "ClothesHorse," Finishing Line Press.) Recent work is forthcoming from Red Hill Paint Quarterly and Toad Suck Review. Find out more: